You've Got Some Nerve(s): Exploring the Spinal Nerves

Posted on 12/7/18 by Laura Snider

At about 45 cm long, the human spinal cord is an information superhighway that connects the brain to the rest of the body. That may seem tiny compared to even the shortest interstate, but the best thing about the spinal cord is that electrical signals (hopefully) don’t get stuck in traffic! In a fraction of a second, pathways of sensory neurons can transmit information from the tip of your toe all the way to your brain.

Like most big highways, the spinal cord also has “exits” that lead to smaller, local pathways. These exits—the spinal nerves—are what we’re going to be focusing on here. Where are they? What do they connect to? What happens when one of them gets closed down?

In other words, we’re going on a road trip through the nervous system.

Introducing the Spine

The first step on our journey along the spine is understanding its components. The spinal cord, encased in connective tissue and supported by the vertebrae, is made up of neural tissue (grey and white matter). The vertebral column, which surrounds the spinal cord, is actually longer than the spinal cord, measuring around 71 cm for men and 61 cm for women. In the average adult human, this column contains 33 vertebrae in five different “sections":

-

7 cervical vertebrae

-

12 thoracic vertebrae

-

5 lumbar vertebrae

-

5 sacral vertebrae (fused to form the sacrum)

-

4 coccygeal vertebrae (fused to form the tailbone)

There are also 23 discs made of gel-like fluid surrounded by cartilage between the vertebrae. They allow for flexibility and shock absorption.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Your Spinal Nerves and You

Now that we know a little more about the spine, let’s zoom in on the nerves that connect the spinal cord and the rest of the body.

First of all, what is a nerve? A nerve is a group of axons of many neurons, all protected by connective tissue (an axon is the long “tail” of a neuron). Outside the brain, axons can get pretty long. The longest neuron in the body extends from the base of the spine to the big toe—a distance that can measure up to a meter!

Spinal nerves are referred to as mixed nerves because they contain both sensory and motor axons. Sensory neurons and pathways report information about the outside world back to the brain, whereas motor neurons and pathways relay orders from the brain back out to the body. This means that spinal nerves are a vital link between the central nervous system (the brain and the spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system (neurons everywhere else).

There are 31 pairs of spinal nerves branching off from the spinal cord, named for the parts of the spine where they attach. The spinal nerves on each side of the body are as follows:

- 8 cervical spinal nerves (C01–C08)

- 12 thoracic spinal nerves (T01–T012)

- 5 lumbar spinal nerves (L01–L05)

- 5 sacral spinal nerves (S01–S05)

- 1 coccygeal spinal nerve (coccygeal nerve)

As you can see in the image below, these nerves “peek out” from the spaces between the vertebrae, which are known as neural foramina (sg. foramen). Usually, a spinal nerve will travel through the foramen above the vertebra that shares its number. So, for example, spinal nerve C04 travels through the foramen between vertebrae C03 and C04.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

As is par for the course in the nervous system, spinal nerves branch almost immediately once they exit the foramina. These early branches are called rami (sg. ramus). Posterior rami go on to innervate the skin and muscles of the back, and anterior rami innervate areas such as the trunk and limbs. The anterior rami do this by forming a plexus, clusters of nerves that then split into “named” nerves that innervate more remote areas of the body.

Typically, the anterior rami that form plexuses are those of the cervical, brachial, lumbar, and sacral spinal nerves. The anterior rami of spinal nerves T01–T011 (and S05 and the Coccygeal nerve), on the other hand, don’t form plexuses. Instead, T01–T011’s anterior rami form the intercostal nerves, which wrap around to the front of the body to innervate the intercostal muscles between the ribs as well as a few abdominal muscles.

The next few sections will take a more detailed look at these plexuses and how they connect to other areas of the body.

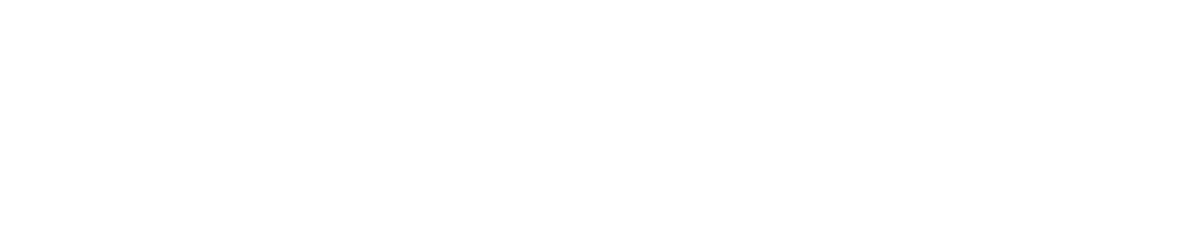

Head, Shoulders…[Cervical Plexus]

The right and left cervical plexuses are made up of anterior rami from cervical spinal nerves C01–C04 and they innervate anterior neck muscles as well as skin on the neck, head, and shoulder(s). Parts of C05 also contribute to the cervical plexus, but C05 isn’t generally considered to be part of the plexus.

The phrenic nerve, made up of axons from C03–C05, is also not technically a part of the cervical plexus. However, it is important to note because it innervates the diaphragm. If you’re breathing (which I hope you are!), you can thank the phrenic nerve. In the image below, you can see how C03–C05 connect to the phrenic nerve and how the phrenic nerve extends downwards to the diaphragm.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Power Cords [Brachial Plexus]

The brachial plexus, composed of the anterior rami of spinal nerves C05–T01, innervate the arms and pectoral girdle. You can use the Latin word for arm, brachium, to remember this!

The brachial plexus is a bit more complex than the cervical plexus because its nerves divide and reunify several times on the way to their destinations. First, the nerves of the brachial plexus form trunks, which each split into anterior and posterior divisions. Then, portions of these divisions unify again to form three cords.

In this image, you can see the spinal nerves exiting the foramina and forming the upper, middle, and lower trunks.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Here’s a fun fact! Nerves from the anterior division of the brachial plexus generally innervate muscles that flex parts of the arm, and nerves from the posterior division of the brachial plexus usually innervate muscles that extend parts of the arm.

Below, each trunk splits into its two divisions, and the posterior, medial, and lateral cords are formed. You can also see how the nerves dip under the clavicle as the trunks split and reunify into the cords.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

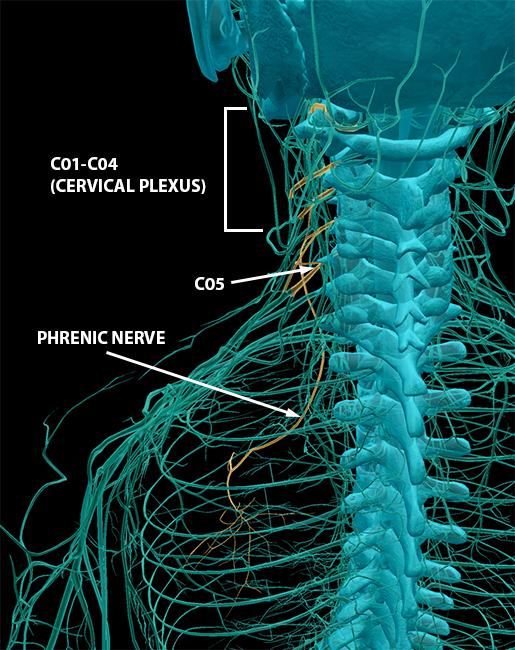

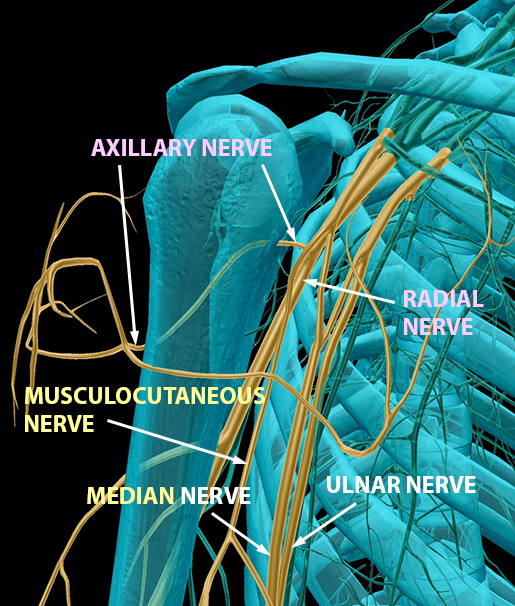

Finally, you can see the main terminal branches of each cord—that is, the “named nerves” that connect back to the spinal nerves of the brachial plexus.

Images from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Portions of C05–T01 form the posterior cord. Its first terminal branch is the axillary nerve, which innervates muscles, such as the deltoids, in the upper arm. Its other terminal branch is the radial nerve, which innervates posterior arm muscles, such as the triceps.

Portions of C08–T01 form the medial cord, which has two(ish) terminal branches. The first of these branches is the median nerve, which also contains portions of the lateral cord. This nerve is responsible for innervating most of the anterior muscles of the upper arm. If you’ve ever whacked your “funny bone” on something, you know what it feels like to hit your ulnar nerve, the other terminal branch of the medial cord.

Lastly, portions of C05–C07 form the lateral cord. Its terminal branches are the median nerve discussed above and the musculocutaneous nerve (try saying that five times fast!), which innervates more anterior arm muscles.

... Knees... [Lumbar Plexus]

Now we’re going to travel down to the lumbar spine and some of the spinal nerves responsible for innervating muscles in the legs and pelvis. The anterior rami of L01–L04 form the lumbar plexus, which innervate the muscles of the thigh and skin of the inside of the leg.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The nerves of this plexus also divide into anterior and posterior portions. The femoral nerve, which innervates such anterior thigh muscles as the quadriceps femoris (knee extensor) and the hip flexors, is the main branch of the anterior division. The main branch of the posterior division is the obturator nerve, which innervates the thigh adductors (medial thigh muscles).

… and Toes (Indirectly) [Sacral Plexus]

The sacral plexus is composed of the anterior rami of L04–S04 and it has anterior and posterior divisions. Nerves from the anterior division tend to innervate muscles that participate in flexion or plantarflexion in the lower limb, whereas nerves from the posterior division tend to innervate muscles that participate in extension or dorsiflexion. Together, these nerves innervate the pelvis, gluteal region, perineum, and much of the leg.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

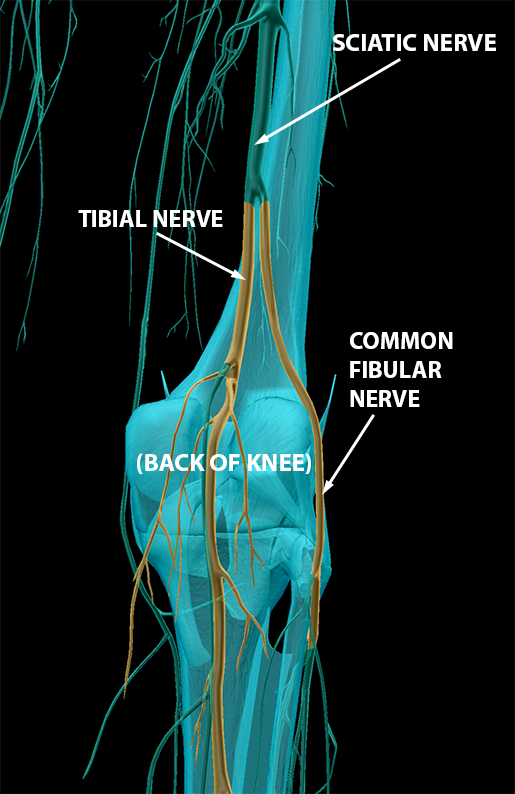

When the powers of the anterior and posterior portions of the sacral plexus combine, they form the sciatic nerve. This nerve may not be a superhero (Captain Sciatic Nerve doesn't have the greatest ring to it), but it is the largest and longest nerve in the body, so it does a lot of work to keep the body running right.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The anterior portion of the sciatic nerve forms the tibial nerve.

The posterior portion forms the common fibular nerve, which splits into the deep fibular nerve and the superficial fibular nerve. These innervate many anterior and lateral muscles of the leg, respectively.

Images from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Images from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Injury to Spinal Nerves — It's "Radiculous"

You may be asking yourself what happens when something goes wrong with the spinal nerves. For now, we’re going to focus on two examples—one involving a pinching of a spinal nerve, and the other involving a disease that impacts the spinal nerves.

Radiculopathy is the condition that arises when a spinal nerve is pinched. Symptoms often include tingling, pain, loss of feeling, or muscle weakness in the regions of muscle and skin innervated by that nerve.

Let’s consider sciatica (injury to the sciatic nerve, aka lumbar radiculopathy) as an example. Sciatica is frequently caused by a slipped or herniated disc. What does that mean? Sometimes the outside of the disc (fiber) wears down, and the inside of the disc (gel) gets pushed to the side, where it can push on the root of a spinal nerve. When a slipped disc presses too hard on the roots of the sciatic nerve, this often causes pain in the buttock and thigh on one side. Surprise, surprise—these are areas innervated by the sciatic nerve!

Shingles (herpes zoster) is a case in which dermatomes in particular are affected. A dermatome is the region of skin supplied by a spinal nerve. Essentially, shingles happens when the chicken pox virus (varicella-zoster) gets into the posterior root ganglion of one or more spinal nerves and lies dormant in the body, often for many years. When the virus becomes active again, the dermatomes of the affected spinal nerves develop a painful, itchy rash.

To see how shingles affects dermatomes, take a look at the map of common areas where shingles rashes occur side by side with a dermatome map of the body. The comparison is striking. For example, the patches going around the ribs looks similar to the stripe-like pattern of the dermatomes of the thoracic spinal nerves.

Map of common areas afflicted by shingles:

Images from cdc.gov

Images from cdc.gov

Dermatome mapping:

Images from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Images from Human Anatomy Atlas.

That's All, Folks!

Congratulations on completing a whirlwind tour of the spinal nerves, their plexuses, and some of the key nerves they feed into in other areas of the body. You can now navigate the highway of the spinal cord as well as the main roads that branch off from it.

P.S. If you want to learn how to make images like the ones in this article using Human Anatomy Atlas, check out this video!

To view a 3D Tour of the images in this blog post using Human Anatomy Atlas 2021 or later...

- Copy this link: https://apps.visiblebody.com/share/?p=vbhaa&t=4_1117_637333946496787390_89951

- Use the Share Link button in the app.

- Paste the link to view the tour.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you a professor (or know someone who is)? We have awesome visuals and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources:

- How does the spine work?

- Info about the longest neuron in the body

- McKinley, M. P., O'Loughlin, V. D., & Bidle, T. S. (2013). Anatomy & Physiology: An Integrative Approach.

- Radiculopathy: Johns Hopkins Medicine

- Sciatica: Johns Hopkins Medicine

- Shingles: Signs and Symptoms